Boston

Nomad Chronicle Part Two

You can cross a country, but you can’t outrun yourself. I left Seattle thinking a change of scenery might change the script, but Boston was just a new stage for an old story. I went there chasing a ghost, the fragmented idea of a father I’d constructed from a handful of memories. The goal was connection, maybe even a son’s need to know his father. What I found was a slammed door, the brutal indifference of a city built on brick and history, and a new kind of family forged in the filth and fury of the punk rock underground.

The journey itself was a descent. We were four strangers crammed into a rattling 1970-something diesel BMW, a car that seemed to run on sheer stubbornness. The air inside was a thick cocktail of diesel fumes, chain-smoked cigarettes, and the unwashed scent of four people living in each other's pockets. We drove east across the northern plains, a landscape so vast and empty it felt like the world had been scraped clean. Days bled together in a hypnotic cycle of greasy spoon diners, gas station coffee that tasted like battery acid, and fitful sleep at desolate truck stops, the rumble of idling engines a constant lullaby. The German drove with a manic intensity, the French woman smoked cloves, and the Canadian woman seemed to exist in a Zen-like state of detachment. I was just the quiet American, watching the country I thought I knew dissolve into a monotonous blur outside the grimy window. By the time we limped across the Canadian border and back down into New England, the car felt less like a vehicle and more like a shared fever dream.

Arriving at my father's door felt like stepping into a foreign country. He lived in a quiet, tidy neighborhood in East Boston. The silence in his house was deafening, a sterile void compared to the chaotic hum of my life. He was a narcissist, his emotions buried under layers of regret and hard living. We circled each other for days, our conversations a minefield of unspoken accusations and long-held resentments. He saw a drifter with ripped jeans and a bad attitude; I saw a stranger who shared my DNA but nothing else. The passion for culinary arts had waned, it had fizzled out. I quit my job. The inevitable explosion wasn't loud, just cold and final. There was no shouting match, just a quiet, dismissive "It's time for you to go." The thud of my backpack and trunk hitting the porch step was the only punctuation needed.

With no money and nowhere to go, I took the first job I could find, working for a guy who bought dilapidated apartment buildings, gutted them, and flipped them. It was brutal, mindless labor. My days were a choking cloud of plaster dust and the deafening roar of power tools. I swung a sledgehammer against century-old lath and plaster, tearing down the walls of other people's lives. My hands were a constant mess of splinters and calluses, and every night I’d collapse onto whatever floor I was sleeping on, my muscles screaming in protest. The work was penance, a way to beat the anger and frustration out of my system. I was tearing things down because I didn’t know how to build anything.

My salvation, if you could call it that, came in the form of a crash pad in East Boston. It was the first and third floor of a triple-decker that shuddered every time a plane took off from Logan Airport. The place was a punk rock flophouse, a chaotic sanctuary for a rotating cast of musicians, activists, and professional fuck-ups. Privacy was a myth. We slept where we fell—on stained mattresses, threadbare couches, or patches of dusty floor. The air was a permanent fog of stale beer, overflowing ashtrays, and the faint, sweet smell of decay. But it was ours. On hot summer nights, we’d climb onto the flat roof, lie on our backs, and watch the bellies of 747s roar just a few hundred feet above us. The sheer, deafening power of it was exhilarating, a thrilling reminder that the world was still moving, even if we weren't.

Our days were a ritual of aimless wandering. We’d scrape together enough change for the T and ride its screeching, rattling cars over to Harvard Square. We were an unwelcome tribe of leather and ripped denim invading the ivy-covered heart of the academic world. We’d spend hours in the Harvard Commons, one of the jewels of the city's "Emerald Necklace" of parks, but to us, it was just a patch of grass where we could get away with drinking cheap beer out of paper bags. We lived on cheddar bread from Au Bon Pain and played endless games of hacky sack, killing time until the sun went down and the city's real life began.

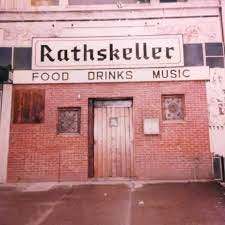

The nights belonged to the music. Boston’s hardcore scene was a different beast than Seattle’s grunge. It was less melodic, more brutal; a pure, concentrated blast of working-class rage. We’d cram ourselves into legendary shitholes like The Rat in Kenmore Square, the air thick with sweat and aggression. Seeing bands like the Dropkick Murphys or The Mighty Mighty Bosstones was a visceral, violent communion. The pit was a swirling vortex of flailing limbs and steel-toed boots, a place where you could unleash all the pent-up fury of a dead-end job and a fucked-up life. It wasn't about nihilism; it was about survival. It was a release valve, a declaration that even if the world had forgotten us, we were still here, and we were still screaming. Boston never felt like home, but in those dark, deafening clubs, surrounded by the angry and the lost, I found a place I belonged.