Cannabis

A History of Healing, Hysteria, and Liberation

For millennia, the relationship between humans and the cannabis plant was one of medicine, ritual, and utility. The ancient Scythians inhaled its vapor in ceremonial steam baths. Hindu texts described it as one of five sacred plants, and its fibers built the sails and ropes that powered the Age of Discovery. Its seeds provided nourishment, and its flowers were used in remedies dating back to ancient China, long before the pharaohs of Egypt. This was a plant deeply woven into the fabric of human civilization. Yet, for the better part of a century, this profound history has been intentionally erased, overshadowed by a manufactured narrative of fear, prohibition, and systemic injustice. Today, as the tide of public opinion and legislation turns, we are not discovering a new panacea, but rather re-evaluating and reclaiming a plant whose benefits we have long known.

For many, including myself, the benefits are not abstract but deeply personal and practical. I use cannabis not to escape reality, but to engage with it more fully, to find the version of myself that feels most whole. It helps me articulate my thoughts with clarity, quieting the chaotic internal monologue that so often accompanies anxiety and ADHD. Where my mind might typically jump between a dozen branching thoughts, cannabis can act as a gentle guide, allowing me to follow a single path of focus from beginning to end. It helps regulate my emotions, transforming the turbulent currents of stress into a manageable flow of creative energy. It doesn't dull my senses; it heightens them. I find myself more engaged in conversations, more focused on my work, more observant of the world around me, and more creative in my solutions—a state of being that feels less like an escape and more like a homecoming.

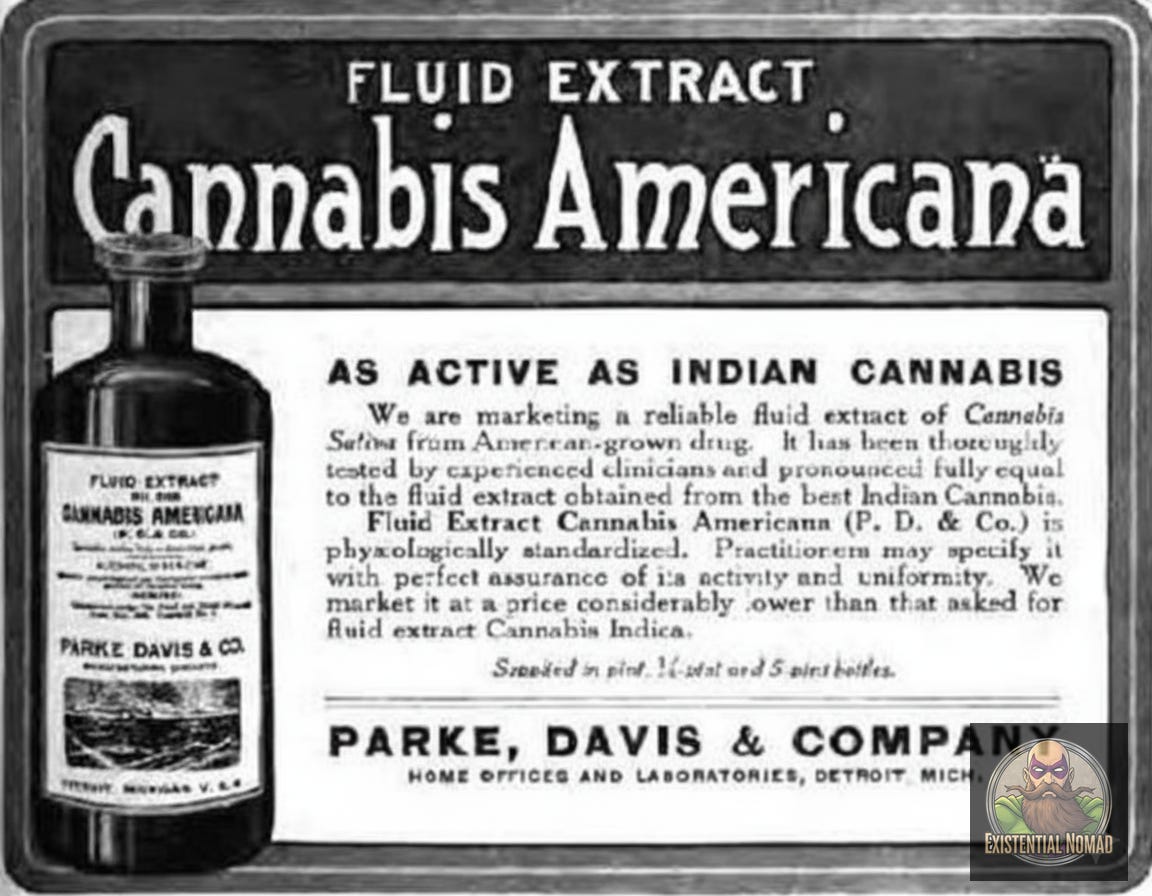

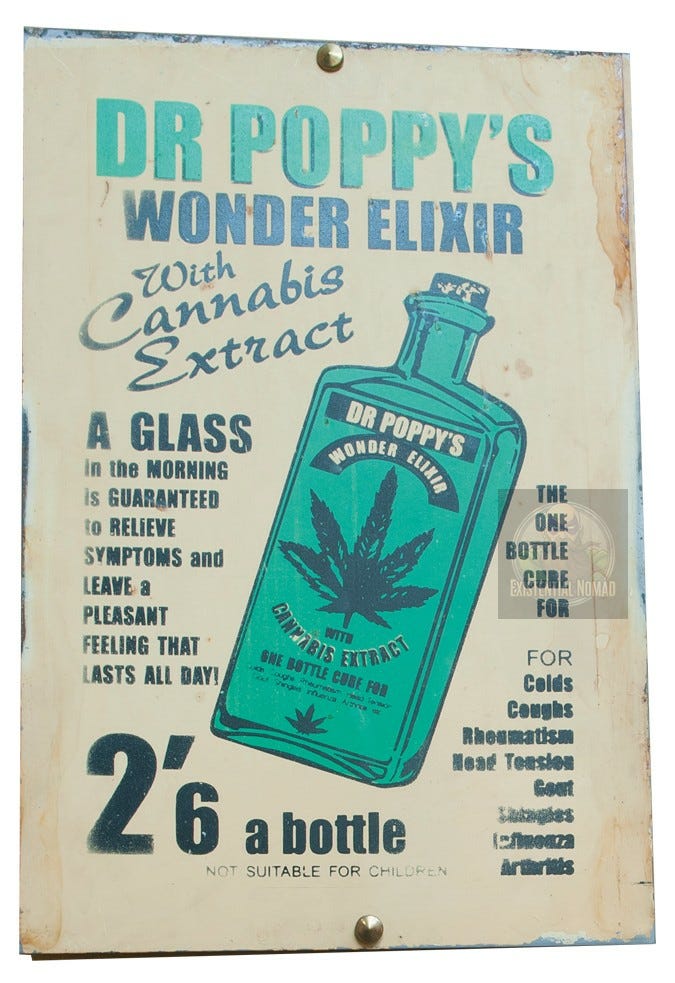

To understand cannabis today, one must understand the calculated campaign that made it illegal. Before the 20th century, cannabis was a common ingredient in the American medicine cabinet, sold openly in pharmacies as tinctures and extracts for everything from insomnia to migraines. Its prohibition was not born from a sudden scientific discovery of its dangers but was instead a meticulously crafted campaign rooted in racial and cultural animus. After the repeal of alcohol prohibition in 1933, the newly formed Federal Bureau of Narcotics, and its ambitious director, Harry J. Anslinger, needed a new villain to justify its existence. Cannabis, then primarily associated with Mexican immigrants fleeing the Mexican Revolution and Black jazz musicians in cities like New Orleans, was a perfect fit.

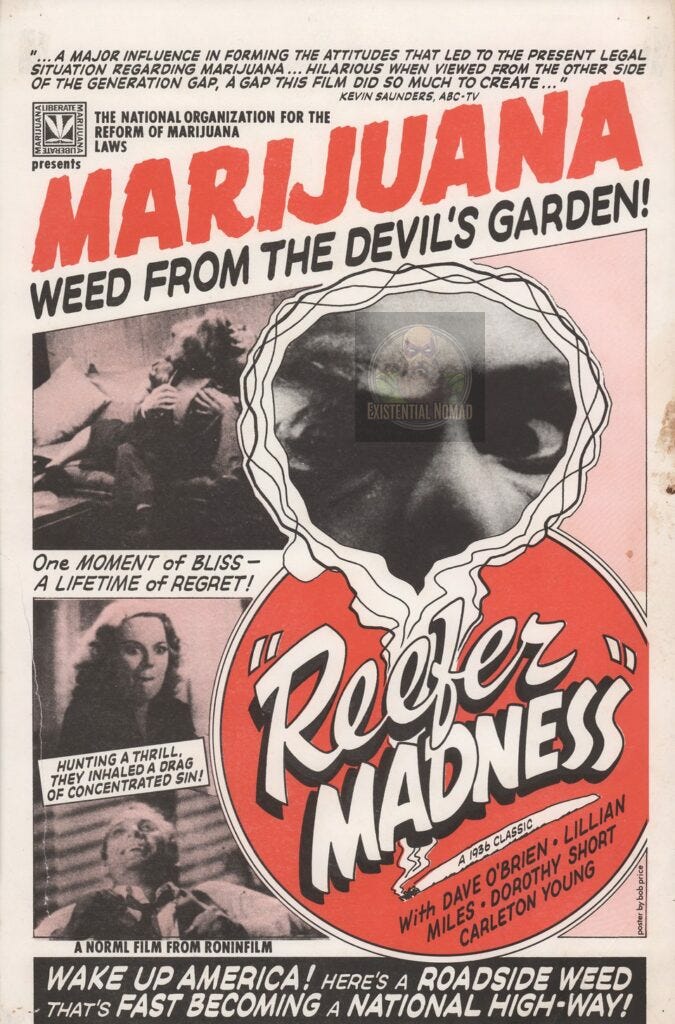

Anslinger, amplified by the national media empires of men like William Randolph Hearst—who had financial interests in the timber industry and saw hemp as a competitor—weaponized xenophobia. The very term "marihuana" was popularized to emphasize its foreignness, supplanting the more clinical term "cannabis." They painted a lurid picture of a "marijuana menace" that would corrupt the nation's youth and incite violence. The propaganda was blatant and vicious, with Anslinger famously stoking racial fears with unfounded claims that cannabis use caused "white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and any others." This racist hysteria, broadcast in sensationalized newspaper articles and films like "Reefer Madness," became the justification for the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, the first step in a long and devastating era of federal prohibition. This campaign culminated decades later in the Nixon administration's "War on Drugs," which used cannabis prohibition as a political tool to disrupt Black communities and anti-war movements, leading to mass incarceration that has disproportionately devastated communities of color for generations.

The Science Behind the Stigma:

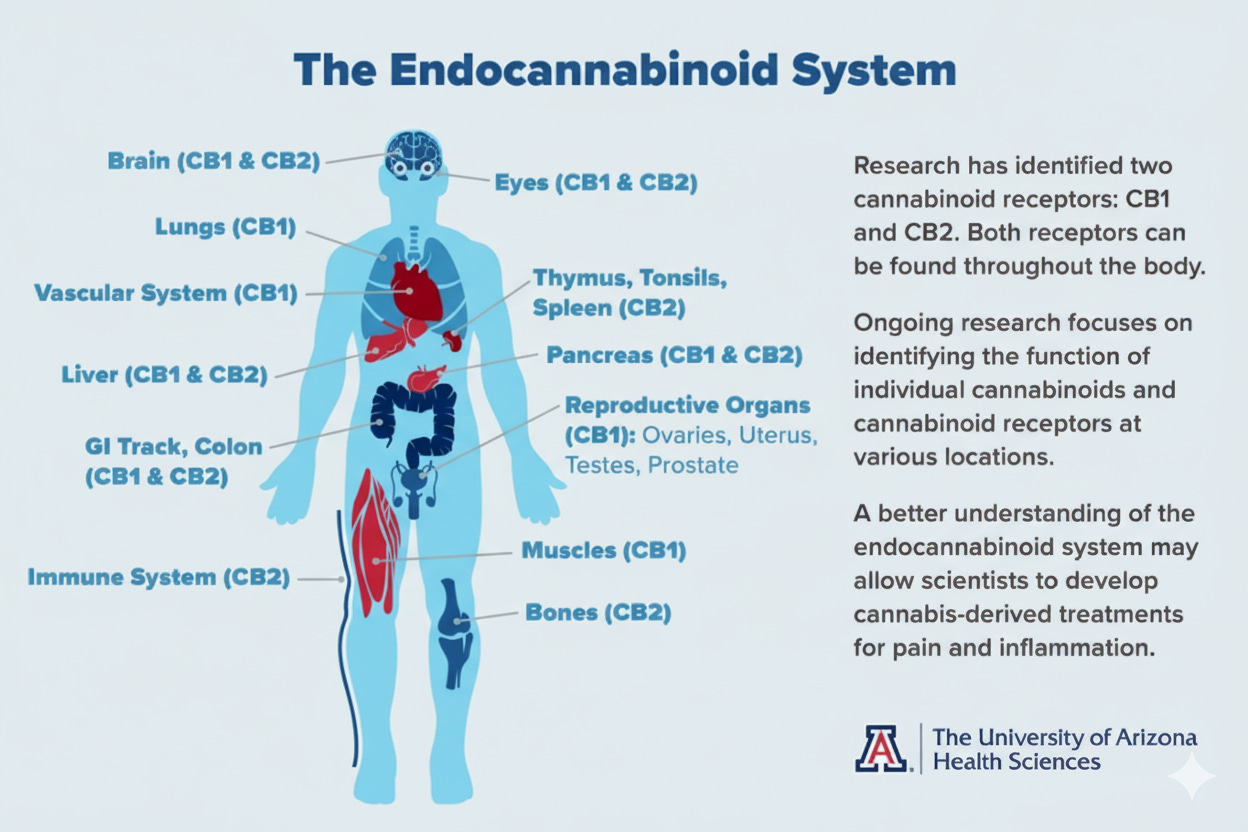

While the government was demonizing the plant, its complex chemistry held profound therapeutic potential. The reason cannabis interacts so intimately with our bodies is because we are hard-wired for it. Every human possesses an Endocannabinoid System (ECS), a complex cell-signaling network that acts as the body's master regulator, helping to maintain balance, or homeostasis. The ECS influences everything from mood and memory to appetite, pain sensation, and immune response. Our bodies naturally produce molecules called endocannabinoids, which are strikingly similar to the compounds found in the cannabis plant.

The cannabis plant contains hundreds of these compounds, but two key groups stand out: cannabinoids and terpenes.

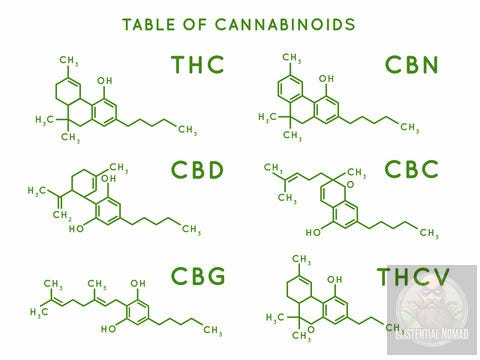

Cannabinoids: The most famous are THC (\Delta^9-tetrahydrocannabinol), known for its psychotropic effects, and CBD (cannabidiol), which is non-psychotropic and celebrated for its therapeutic applications. While THC provides the "high," it also offers significant pain relief and can reduce nausea. CBD, on the other hand, has been shown to have potent anti-inflammatory, anti-anxiety, anti-seizure, and analgesic properties, making it a focus of intense medical research.

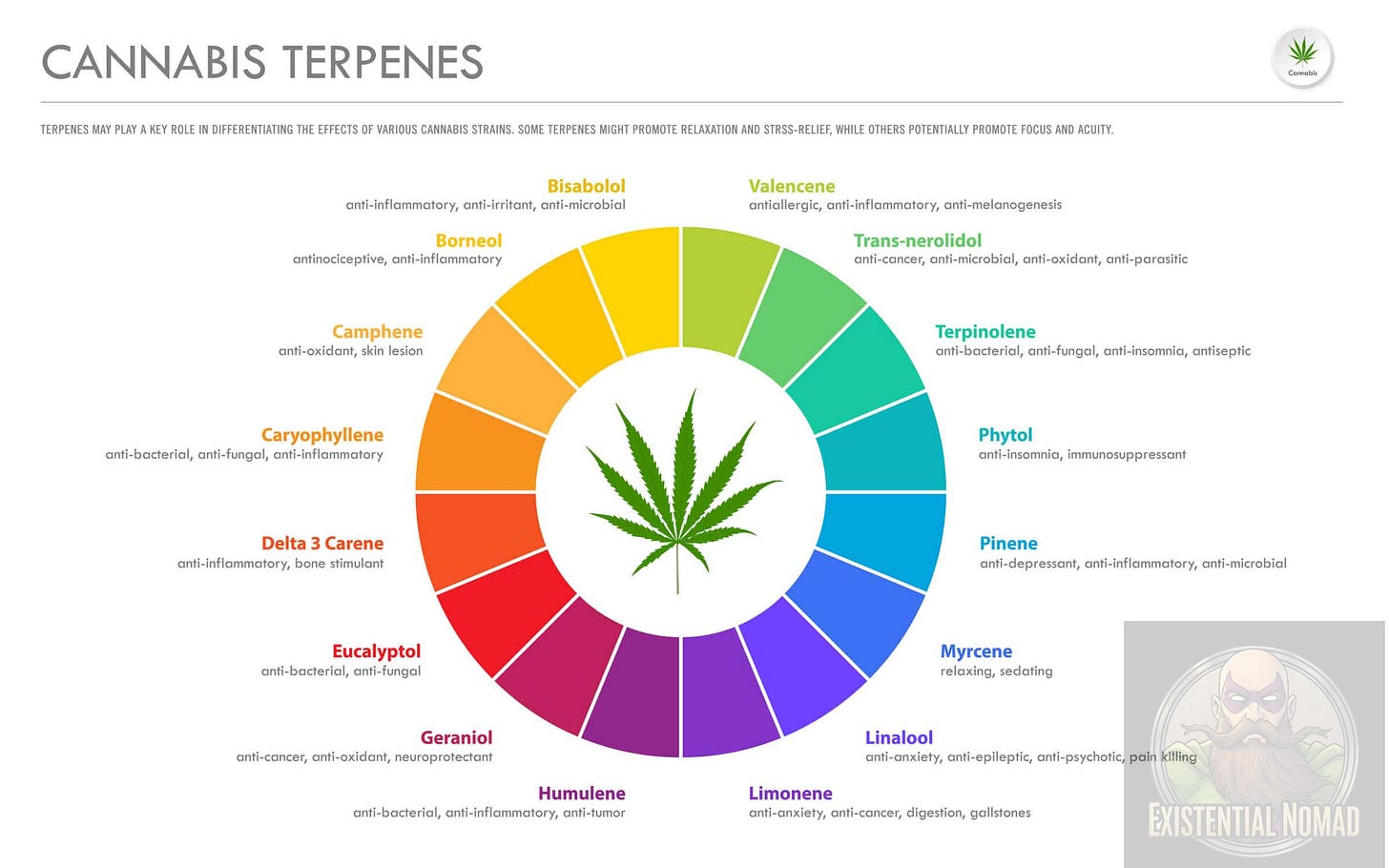

Terpenes: These are the aromatic oils that give different cannabis strains their distinct smells and flavors—from the citrus of Limonene to the pine of Pinene. More than just aroma, terpenes have their own therapeutic effects and work synergistically with cannabinoids in what Israeli researcher Raphael Mechoulam, who first isolated THC, dubbed the "entourage effect." For example, the terpene Myrcene can have sedating effects and may enhance the pain-relieving properties of THC. Limonene may elevate mood and relieve stress. This intricate interplay is what makes specific strains better suited for specific medicinal or personal needs.

The very framework of prohibition has made studying these compounds incredibly difficult. By classifying cannabis as a Schedule I drug—a category reserved for substances with "no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse," alongside heroin and LSD—the federal government created monumental barriers for researchers. For decades, U.S. scientists were restricted to studying a single, notoriously low-quality supply of cannabis grown at the University of Mississippi, which bore little resemblance to the products available in legal markets.

Ironically, while publicly denying its medical value, the U.S. government ran a compassionate Investigational New Drug (IND) program from 1978 to 1992. This program provided a handful of patients with a monthly supply of government-grown cannabis to treat severe conditions, a tacit admission of its medicinal efficacy. Lacking robust domestic data, early proponents of legalization relied heavily on international studies, particularly those conducted by research pioneers in Israel, to build their case. The Ultimate Civil Liberty

As we dismantle the legal and social architecture of prohibition, we are doing more than just correcting a historical wrong; we are confronting fundamental questions of freedom. The choice for a consenting adult to use cannabis, whether for medicinal relief, mental health, or personal well-being, is an act of bodily autonomy. It is a declaration that the individual, not the state, is the ultimate authority over their own consciousness and body. Forcing a patient to choose between an addictive opioid and a natural plant, or arresting an adult for cultivating a plant in their own home, is a profound government overreach.

The fight for cannabis legalization is a fight for cognitive liberty. The story of cannabis is a story of human history, scientific discovery, and a long, arduous fight for justice. It serves as a powerful reminder of how easily fear and prejudice can be codified into law, and how those laws can be used to persecute marginalized communities. As we move forward, the challenge is not only to legalize but to do so equitably, ensuring that the communities most harmed by the War on Drugs have a meaningful opportunity to participate in the burgeoning legal industry. The leaf is being reclaimed, and with it, a more honest, compassionate, and holistic approach to wellness and personal freedom.