Seattle

Nomad Chronicle Part One

Seventeen is the perfect age for a disappearing act. You're old enough to pass for an adult in a dimly lit bar, but still young enough that running away feels like an adventure, not a failure. My grand escape from a pre-packaged suburban future began with the smell of hot grease and the drone of ferryboats. I'd landed on Mackinac Island, a living postcard of a place, taking a job as a line cook at Watersmeet. By day, I was a cog in the tourism machine, flipping burgers for families in pastel shorts, the forced cheerfulness of the island a constant, low-grade irritation. The real world only began after my shift, when I’d peel off my stained apron and head back to the cinderblock purgatory of employee housing.

That's where I found my people—a loose tribe of fellow exiles, all running from something. Our sanctuary was a common room with faded, worn, and stained carpeting, and a TV that only received two channels. We’d sit for hours under the buzz of a dying fluorescent light, the air thick with the smoke of cheap weed and the sounds of playing euchre into the wee hours. My roommates from Bay City were my high priests of grunge. They were the ones who pushed a worn cassette Nirvana Bleach into my hands, the raw, sludgy distortion cutting through the Michigan humidity and rearranging my DNA. We were kids playing at being adults, fueled by cheap beer and a shared certainty that our real lives were waiting for us somewhere else.

When the island shut down for the winter, I drifted back to my hometown of Grand Rapids, a place I no longer recognized. I found a new home in a sprawling, dilapidated hotel known as The Enclave, a punk rock commune teetering on the edge of collapse. The place was a beautiful wreck, with peeling paint, a permanent smell of stale beer, and a roster of transient tenants. Our claim to fame was the punk shows we hosted in the cavernous, damp basement. It was a chaotic ritual of sweat and noise, a tightly packed slam pit of bodies crashing against each other in the dark. I made my rent by running an under-the-table café from the kitchen, serving lukewarm coffee in chipped mugs to kids with safety pins in their jackets. It was a life, of sorts. But the punk scene’s three-chord fury felt like a dead end. It was anger for anger’s sake. The music bleeding from my speakers, the sounds from Seattle, had something more: a melodic, soul-crushing despair that felt more honest, more real. The pull became an obsession, a physical need.

I packed all my stuff into a frame backpack and a steamer trunk, and bought a one-way bus ticket west. The days-long journey was a grimy marathon of stale truck-stop coffee and the faces of strangers who looked as worn out as the cracked vinyl seats. Stepping off the bus into the Seattle Greyhound station wasn't a triumphant arrival; it was an immersion into a world of grey. The sky was a low, oppressive ceiling of bruised-looking clouds, and a constant, fine drizzle seemed to emanate from the pavement itself. This wasn’t just rain; it was an atmosphere, and it soaked through my jacket and into my bones.

For the first three months, my entire existence was confined to a few blocks around the city youth hostel. Home was a bottom bunk with a mattress as thin as a yoga mat, the metallic squeak of the frame a constant companion. The place was a repository for the world's lost children—runaways from the Midwest, backpackers from Australia, kids who had aged out of the foster system. The air was a cocktail of damp laundry, instant noodles, and quiet desperation. I was utterly, terrifyingly alone. My days were spent nursing a single cup of coffee at a diner, reading the free weeklies to find a job, any job. I survived on day-old bagels and the sheer, stubborn refusal to admit I'd made a catastrophic mistake. The loneliness was a physical weight, a crushing silence in a city humming with life.

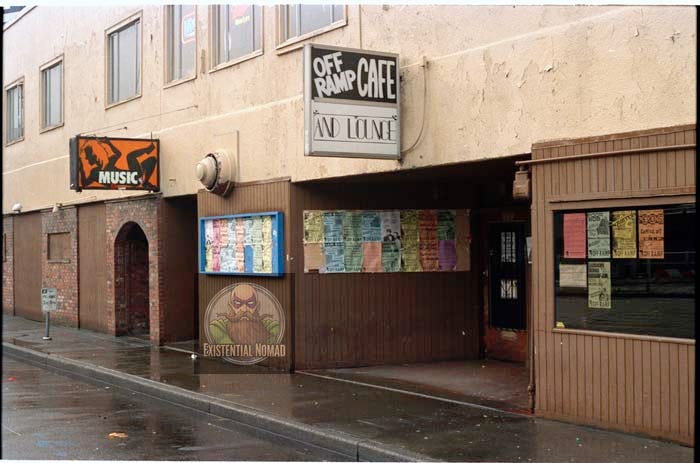

My salvation, and my real reason for being there, was the music. The cover charge to a club was the best money I could spend. It was an entry fee into another world. I became a ghost in the hallowed stage of the Off Ramp and The Crocodile Cafe, dark, sweaty boxes where the air was too thick to breathe and the floors were permanently sticky with the ghosts of ten thousand spilled beers. I’d stand in the back, nursing a cheap beer for two hours, and just watch. I saw the unholy energy of Nirvana, the way the crowd would surge forward as one organism when they launched into "Breed," a wave of flannel and fury. I felt the floor tremble from the sheer sonic weight of Soundgarden, Chris Cornell's voice a force of nature that could strip paint from the walls. This wasn't a performance; it was an exorcism. We were all there for the same reason: to feel something, anything, in a world that felt increasingly numb.

The scene was more than just the bands. It was the culture they spawned. It was the thrill of finding a zine someone had left on a coffee shop table, filled with passionate, badly-typed reviews. It was spending an hour you didn’t have at Tower Records, flipping through CD longboxes, the artwork a portal to another sound. It was the shared uniform of ripped jeans, faded band shirts, and steel-toed Doc Martens that made you feel part of an army. After the shows, the crowd would spill out onto the wet pavement, ears ringing, and disperse into the night, or head to a 24-hour diner like the Dog House to chain-smoke and dissect every single moment of the set we'd just witnessed.

You couldn't live in that environment and not become politicized. My radicalization didn't come from a pamphlet; it came from the pavement. It was seeing the homeless Vietnam vets huddled under the viaduct, the strung-out junkies with haunted eyes, the clear line being drawn between the city’s gritty, authentic soul and the sterile corporate campuses of Microsoft that were beginning to metastasize across Lake Washington. The anger and alienation in the music wasn’t an abstraction. When Layne Staley sang about decay, you could see and smell it in the alleys. When Kurt Cobain screamed about being cheated, you felt it in the low-wage, dead-end jobs that were all you could find. It was a politics born from experience—an anti-corporate, anti-authoritarian snarl that saw the system for the joke it was. Seattle wasn't a place I moved to; it was a place that broke me down, stripped me of my naïve ideas, and rebuilt me into someone who understood that sometimes, the only rational response to the world is to scream.

Sounds about right lol. Growing up in the 80s, I remember peddling my banana seat bike from Tacoma through Lacey. There was always an adventure; an escape.