The Revolution Delusion

The logistical reality of why white America isn't ready for collapse.

A leftist creator I follow planted the seed “White People Aren’t Ready For Revolution.” I agree with this statement, and it has sat in my brain rent-free until now.

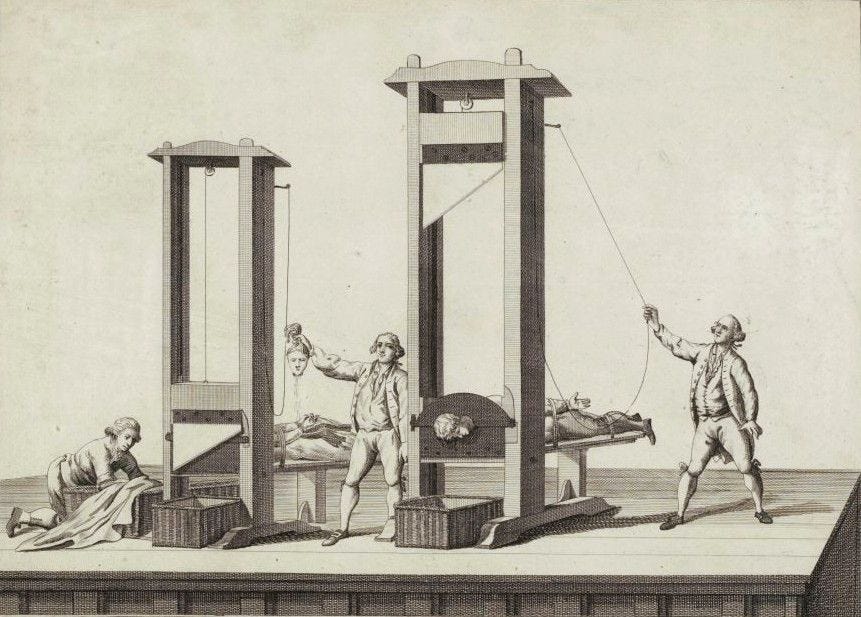

In the current American political landscape, the word “revolution” is frequently invoked by the left as a moral necessity, while “civil war” is increasingly romanticized by the radical right as an inevitable purge. However, a stark divide exists between the rhetoric of conflict and the logistical reality of survival. As the nation grapples with the rise of authoritarian tendencies and systemic failures, a critical question emerges: who is actually prepared for the collapse of the status quo? The uncomfortable truth is that the white population, across the political spectrum, is largely ill-equipped for the very upheaval they discuss.

For much of the white population in America, the concept of revolution is more theoretical than practical.

Decades of relative systemic stability have created a deep dependency on modern infrastructure that functions as a golden cage. This dependency includes a reliance on constant access to electricity, high-speed internet, and global supply chains, alongside a lingering belief that the system is ultimately self-correcting. This institutional faith has, in many ways, allowed fascist ideologies to take root within democratic structures; because the system provides a baseline of comfort, the urgency to dismantle it before it turns predatory is often blunted by the fear of losing that comfort.

Unlike marginalized communities, many affluent white demographics lack established, non-governmental support networks—the mutual aid essential for surviving a breakdown in state services. Mutual aid is not charity; it is a horizontal exchange of resources and services for the sake of collective survival. In the absence of a functioning grocery store or a state-run power grid, most people in the suburbs would find themselves without the skills or the community ties necessary to secure food, water, and medicine. They are addicted to the infrastructure the government provides, even when that infrastructure is crumbling or being used as a tool of state control.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, the “America First” movement and various white nationalist factions have increasingly adopted the language of civil war. This rhetoric often masks a desire for violence against BIPOC and marginalized communities, fueled by a romanticized vision of being the “heroes” of a new, segregated order. These “gun nuts” often operate under the delusion that the Second Amendment is a shield that applies only to them. However, they frequently overlook a critical tactical reality: the U.S. military. Any domestic uprising would not merely be a clash between civilian factions but a confrontation with a global superpower that is sworn to uphold the Constitution against all enemies, domestic or otherwise.

Furthermore, the assumption that marginalized communities are unarmed is a significant strategic miscalculation. Firearm ownership among minority groups has seen a sharp increase in recent years, driven by the very threats issued by white supremacist groups. The “civil war” crowd thinks they will be the only ones at the table, but the rest of the Constitution still applies, and the communities they target have been preparing for the worst-case scenario for a very long time.

Perhaps the most significant oversight in the revolutionary fantasy is the inherent resilience of those who have already been forced to live outside the system’s primary benefits. BIPOC and First Nations communities have, by necessity, spent generations building networks of survival. Because these groups have been intentionally marginalized—politically, socially, and financially—they have developed robust mutual aid systems that do not rely on the grace of the state. They have survived the “end of the world” multiple times over through colonization, Jim Crow, and systemic divestment.

These communities are often better equipped to handle the loss of “normalcy” because it has never been guaranteed by the state. While white folks are arguing over the nuances of political theory or stocking up on gadgets that require a functioning power grid, First Nations people and marginalized urban communities are practicing the skills of communal care and resource management that become the only currency in a collapsed society.

The tension is reflected in shifting demographics and social participation.

To understand the scale of the groups involved, consider the following data points regarding the American landscape:

Approximately 40% of the U.S. population identifies as a racial or ethnic minority.

Firearm purchases by Black Americans rose by 58% compared to the previous year.

Roughly 37.9 million Americans live in poverty; these populations are statistically more likely to rely on community-based aid.

Mutual Aid Growth Since 2020, over 800 new formal mutual aid networks have been documented in urban centers.

The rise of American Fascism is, in part, a reaction to the realization that the old systems of control are failing. While modern fascists struggle to dismantle the Constitution, they are finding ways to bypass it through the judicial system and local legislation. Far too many people believe the system can be “fixed” through traditional means, failing to see that the system is functioning exactly as intended to protect the interests of a few. This belief in reform acts as a sedative, preventing the formation of the very networks that would be needed if—or when—the system finally breaks.

Whether it is a revolution to dismantle a tyrannical government or a civil conflict sparked by extremist ideologies, the result would be the total evaporation of the American “way of life.” While the radical right romanticizes the gun, and the comfortable left theorizes about change from the safety of their laptops, it is the marginalized communities—those already seasoned by systemic struggle—who possess the actual infrastructure of survival. Until the broader white population recognizes its own fragility and the necessity of mutual aid over systemic addiction, the talk of revolution remains a dangerous abstraction that they are wholly unprepared to survive.